By Laurie Johnson. . June 18, 2009.

Over three decades of experience with environmental regulation show that investments in environmental protection, coupled with GDP growth, led to an increase in jobs that were orders of magnitude larger than any job losses caused by environmental requirements. The dire job loss predictions by industry simply never came to pass. Instead, tens of thousands of new jobs were created every year, much more than the job reductions per year that various government agencies and academic analyses found after the fact, in only a few sectors.[1] We detail the data further below.

Wind the tape back to before environmental regulations were passed, and we see that the opponents of the day, just like today's climate obstructionists, made dire job loss forecasts. They never came true.

Consider the following claim from a study sponsored by the U.S. Business Roundtable in 1990, typical of industry-backed studies of past environmental regulations:

"Across the [1990] CAA Amendments titles studied...this study leaves little doubt that a minimum of 200,000 (plus) jobs will be quickly lost, with plants closing in dozens of states. This number could easily exceed one millions jobs-and even two millions jobs-at the more extreme assumptions about residual risk." (Hahn and Steger, 1990). (Emphasis in the original).

In fact, studies show that actual gross reductions in jobs were limited to one to three thousand jobs per year, with environmental jobs increasing by the tens of thousands per year.

Studies by today's climate legislation opponents sound the exact same alarm as the study quoted above. Reports by the Heritage Foundation, the Chamber of Commerce, and the National Association of Manufacturers, among others, repeatedly predict that millions of jobs will be lost if climate legislation is passed. But the facts tell us that the opponents of today, like those of the past, are Chicken Littles.

Let's consider the historical evidence in more detail.

In the 1970s, the nation's first comprehensive federal environmental laws were passed. These laws were far reaching, placing significant restrictions on many pollutants. An entire new federal agency, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), had to be created to implement them.

What has happened to the economy and the environment since then?

GDP is more than triple its 1970 level.

Job creation in the environmental protection industry has been equally impressive. Between 1977 and 1991, EPA (1991) estimated that approximately 50,000 new environmental protection jobs per year were created. And between 1997 and 2007, as alternative clean energy markets have increasingly expanded, PEW Charitable Trusts (2009) recently estimated as many as 85,000 jobs per year were created. We could have spent our resources on other goods and services, of course, but we would have created fewer jobs. The reason is that environmental protection expenditures are more labor intensive than expenditures on other goods in the economy as a whole.

What's more, we can expect an even better outcome from climate legislation: energy efficiency investments, and the reduction in imported oil and energy use that follow, will give us more resources, further increasing the number of jobs possible. In fact, enacting comprehensive clean energy and climate legislation this year will put Americans to work right away insulating homes, building wind turbines, and manufacturing efficient automobiles. And, contrary to opposition studies, this could lead to an increase in wages across the entire economy rather than a decrease: according to a large body of academic research, lower unemployment rates increase average earnings.[2] This positive wage effect is likely to be somewhat stronger at the lower end of the labor market, yet more good news for environmental protection jobs. Entry level jobs requiring low educational credentials account for the largest share of jobs within the environmental protection industry. This is especially true for clean energy investments, investments that also provide a larger number of jobs at every level of expertise than equivalent expenditures in fossil fuel energy (Pollin et.al., 2009).[3]

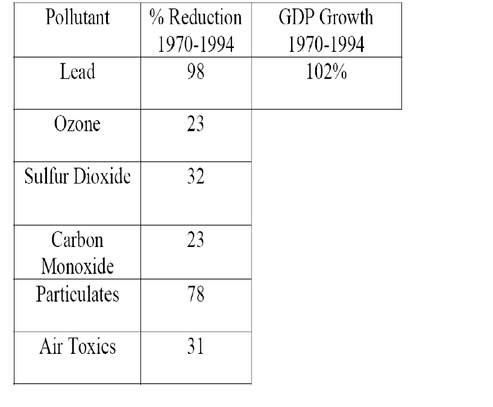

We also can boast tremendous health and environmental benefits: our investment in protecting the atmosphere more than paid off. Consider the following record of success from EPA's 25th anniversary report (1996):

In a retrospective study, the EPA estimated that from 1970 to 1990, these health and environmental improvements delivered $36 trillion dollars (2008$) in benefits, at a cost of only $851 billion dollars (2008$). These gains came from improved health and productivity, reducing medical costs and increasing our standard of living. The accomplishment is all the more impressive given the simultaneous increase in GDP and economic output.

The reductions in the above table occurred over the space of 24 years. In comparison, climate legislation is calling for a reduction in pollution that causes global warming of approximately 17% by 2020, and 83% by 2050, giving us 12 and 38 years, respectively, to achieve our targets. Given our past performance, these goals certainly seem manageable.

What about those predicted job losses resulting from increased costs of production due to environmental requirements? Survey results from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s have consistently found gross employment losses on the order of 1,000 to 3,000 jobs per year nationwide (the figure cited in the introduction) resulting from pollution control requirements. Relative to other reasons for job losses, these are practically invisible: every year approximately 9,500 layoffs result from adverse weather events, and over 450,000 from seasonal changes in employer demand for workers (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1995-1997 survey data). Contrast this to claims by opponents of environmental regulation ("millions" of job losses), and the annual 50,000+ jobs created in environmental protection, and one can only conclude that the catastrophic job losses predicted by climate obstructionists are just plain wrong.

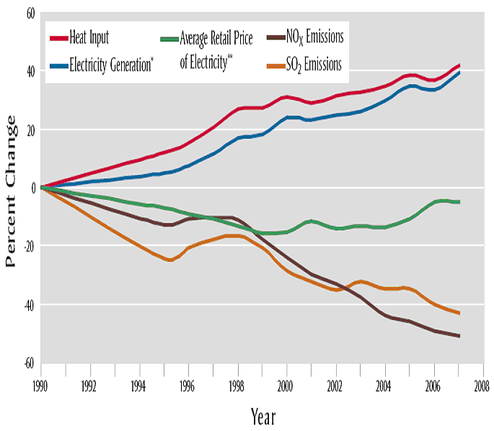

Contrary to alarmist opposition estimates (and even the more moderate government analyses), electricity prices didn't go through the roof. In fact, they actually went down slightly, while combustion of fossil fuels ("heat input") and electricity output increased. The figure below, taken from a 2007 progress report from the EPA, tells the story:

What can we conclude?

Today's job scare studies all show that the economy expands steadily and strongly with new climate protection laws (a result they try to conceal through distorted presentation). In the face of the economic growth their own models predict, the scare mongers have no credible explanation for these claims of job losses. Based on over three decades of experience with environmental regulation, we can be confident that industry scare tactics are no truer today than they were in the past.

References

Bartik, Timothy (2001). Jobs for the Poor: Can Labor Demand Policies Help? New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

---(2000). The changing effects of the economy on poverty and the income distribution. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

---(1994). "The effects of metropolitan job growth on the size distribution of family income," Journal of Regional Science, Vol 34(4), pp. 483-501.

---(1991). Who benefits from state and local economic development policies? (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research).

Blank, Rebecca M. and David Card (1993). "Poverty, income distribution, and growth: Are they still connected?" Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (2), pp. 285-339.

Card, David (1995). "The wage curve: A review," Journal of Economic Literature (33), pp. 785-99.

Goodstein, Eban (1996). "Jobs and the Environment: An Overview." Environmental Management 20(3): 313-321.

---(1999). The Trade Off Myth: Fact & Fiction About Jobs and the Environment (Washington D.C.: Island Press).

Hines, James R., Hoynes, Hilary, and Alan B. Krueger (2001). "Another look at whether a rising tide lifts all boats," National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 8412 (August).

Hahn, Robert, and Wilbur Steger (1990). An Analysis of Jobs at Risk and Job Losses from the Proposed Clean Air Act Amendments (Pittsburgh: CONSAD Research Corporation).

Kieschnick, Michael (1978). Environmental Protection and Economic Development (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economic Development Administration).

PEW Charitable Trusts (2009). The Clean Energy Economy: Repowering Jobs, Businesses, and Investments Across America (Washington D.C.: PEW Charitable Trusts).

Pollin, Robert, Wicks-Lim, Jeannette, and Heider Garrett-Petlier (2009). Green Prosperity: How Clean-Energy Policies Can Fight Poverty and Raise Living Standards in the United States (Amherst, MA: Political Economy Research Institute).

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics Division, 1987-1982, and 1995-1997 data.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2009). Acid Rain and Related Programs: 2007 Progress Report (Washington D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation, Clean Air Markets Division).

--(1998). Survey of Environmental Products and Industries (Washington D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Policy Planning and Evaluation).

---(1997). Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act: Retrospective Study 1970-1990 (Washington D.C.: U.S. EPA).

---(1996). U.S. EPA's 25th Anniversary Report: 1970-1995.

Wykle, Lucinda, Morehouse, Ward, and David Dembo (1991). Worker Empowerment in a Changing Economy: Jobs, Military Production, and the Environment (New York: Apex Press).

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Goodstein (1996, 1999); U.S. Department of Commerce (Kieschnick, 1978); Wykle et. al. (1991).

[2] A range of estimates exist on the impact of unemployment on earnings. For example, Bartik's 2001 survey of five studies (Bartik 1991, 1994, 2000; Blank and Card 1993; Card 1995) provides a range of a 1.5 to 3.5 percent increase in average real earnings when the unemployment rate falls by 1 percent. Additionally, Bartik's 2001 study estimates that the average household experiences a 1.9 percent increase in real earnings when the unemployment rate falls by one percent. Finally, Hines, Hoynes, and Krueger (2001) estimate that the average family earnings increases by 1.3 percent for every one-percent fall in the unemployment rate. A simple average of the seven estimates produced by these various studies suggests that the impact of a 1 percent decline in the unemployment rate produces approximately a 2 percent rise in earnings. The reason for this effect is that when the demand for labor increases and the unemployment rate falls, workers have more bargaining power.

[3] This higher proportion of entry level jobs results in lower average wages in the clean energy sector than the fossil fuel sector. However, in absolute terms, more jobs are created for every level of experience within the clean energy sector.

This post originally appeared on NRDC's Switchboard.

Laurie Johnson is Chief Economist at the Climate Center of the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington DC. Prior to joining the NRDC in May 2008, Johnson was a professor in the economics department at the University of Denver for eight years. Her research in environmental and natural resource economics, experimental economics, and poverty and welfare, appeared in academic and popular journals. At NRDC, Johnson's work has focused on macroeconomic modeling of climate change legislation, as well its distributional impacts. She received her PhD in economics from the University of Washington, Seattle.

Add new comment